| Table of Contents On-Line Hawaiian Dictionaries || Authors: Scott Anthony | David Aguirre | Jim Allen | Dick Ash | Vernon Bartlett | H. Beattie | Mark Blackburn | John R. K. Clark | Trevor Cralle | Timothy DeLaVega | DiMauro & Kugelberg | Peter Dixon | Lázaro Echegaray Eizaguirre | P. Ellam | El Paipo | J.C. Elwell | Steve Estes | Midget Farrelly | Ben R. Finney | Joseph "Skipper" Funderburg | Ronald S. Funnell | Robert Gardner | Thomas Hickenbottom | Joseph James | Mark Jury | Duke Kahanamoku & Joe Brennan | Drew Kampion | John Kelly | H. Arthur Klein | Beatrice Krauss | Cameron Kirk | Peter Kreeft | G.W. Kuhns | Lindsay Lord | Margan & Finney | Mary L. Martin | Guy Motil | Desmond Muirhead | William Desmond Nelson | Max Nodaway | Charles Nordhoff | José de Olivares | George Orbelian | Otto B. Patterson | Steve Pike | John Severson | Tina Skinner and Mary Martin | St. Pierre, Brian | Thomas Thrum | Herb Torrens | Michael Walker | Wayne Warwick | Unknown authors | |

Preface to the Annotated Bibliography of Paipo and Bellyboard Surfing This annotated bibliography is a collection of surfriding summaries highlighting the inclusion of paipo and bellyboard surfriding. It is organized by the primary author's last name except for the initial summaries which document early reports of prone surfing. For a list of bibliographical sources reviewed see the Bibliography for Research. The Annotated Bibliography includes direct citations, visual snippets of information of both the written word and images for collective research purposes. Most of the books and booklets also include my own comments and notations. Many of the books included below are very good and informative but possibly not directly relevant to paipo & bellyboard waveriding. General Acknowledgments include many people and organizations that have provided support to the Paipo Research Project. Special thanks to WorldCat.org and the national and worldwide network or libraries that have graciously shared their resources through the Inter Library Loan system and the people that have facilitated access. |

|

Rodriguez, Rodrigo. (1952). Paipo Forever!. Rincon, PR: 2nd Rock Publishing. |

|||

| Title page and Contents [PDF] and Introductory Chapters Source(s) |

|

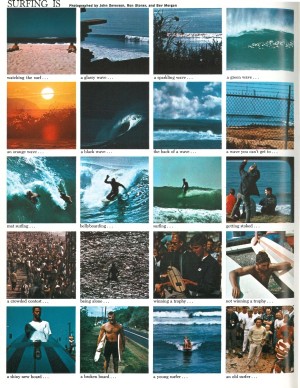

This book on surfing for life is written by an older man, especially for the late-1960s era. Allen states, "I am a 41-year-old family man, a respected community member, and a university professor who holds the Ph.D. degree. I am also a confirmed surfer." This is in contrast to the youthful, rebel stereotypes of the era. He goes on to state, "...most older men look upon surfing as either a frivolous waste of time or an activity appropriate only for youngsters - if for anyone at all." He also talks about surfing as a fad, the increasing commercialism of the sport and paradoxically the high degree of conformity within the surfing community. | |

| Ch. 9, pp. 130-133, Body Surfng and Bellyboarding | Of

the four

pages devoted to body surfing and bellyboarding, 2.5 pages cover body

surfing and 1.5 pages are on bellyboarding. No section covers hand

boarding or kneeboarding. Key passages include:

|

||

| Overall observation | Although published in 1970, the first edition is mostly written in a mid-1960s flavor with a longboard orientation except in the chapter "The Boards." There are tons of photos but none of bellyboarder/paipo riders. The terms bellyboard and paipo ("as they are called in Hawaii) are both used. In the glossary defines paipo, but not bellyboard, "Paipo: the Hawaiian term for a bellyboard. See Chapter 9." There is no real discussion of board lengths, widths, thickness or plan shapes. | ||

Beginning of Entry xxxx

|

Rodriguez, Rodrigo. (1952). Paipo Forever!. Rincon, PR: 2nd Rock Publishing. |

|||

| Title page and Contents [PDF] and Introductory Chapters Source(s) |

|

This book on surfing for life is written by an older man, especially for the late-1960s era. Allen states, "I am a 41-year-old family man, a respected community member, and a university professor who holds the Ph.D. degree. I am also a confirmed surfer." This is in contrast to the youthful, rebel stereotypes of the era. He goes on to state, "...most older men look upon surfing as either a frivolous waste of time or an activity appropriate only for youngsters - if for anyone at all." He also talks about surfing as a fad, the increasing commercialism of the sport and paradoxically the high degree of conformity within the surfing community. | |

| Ch. 9, pp. 130-133, Body Surfng and Bellyboarding | Of

the four

pages devoted to body surfing and bellyboarding, 2.5 pages cover body

surfing and 1.5 pages are on bellyboarding. No section covers hand

boarding or kneeboarding. Key passages include:

|

||

| Overall observation | Although published in 1970, the first edition is mostly written in a mid-1960s flavor with a longboard orientation except in the chapter "The Boards." There are tons of photos but none of bellyboarder/paipo riders. The terms bellyboard and paipo ("as they are called in Hawaii) are both used. In the glossary defines paipo, but not bellyboard, "Paipo: the Hawaiian term for a bellyboard. See Chapter 9." There is no real discussion of board lengths, widths, thickness or plan shapes. | ||

Beginning of Entry xxxx

|

Rodriguez, Rodrigo. (1952). Paipo Forever!. Rincon, PR: 2nd Rock Publishing. |

|||

| Title page and Contents [PDF] and Introductory Chapters Source(s) |

|

This book on surfing for life is written by an older man, especially for the late-1960s era. Allen states, "I am a 41-year-old family man, a respected community member, and a university professor who holds the Ph.D. degree. I am also a confirmed surfer." This is in contrast to the youthful, rebel stereotypes of the era. He goes on to state, "...most older men look upon surfing as either a frivolous waste of time or an activity appropriate only for youngsters - if for anyone at all." He also talks about surfing as a fad, the increasing commercialism of the sport and paradoxically the high degree of conformity within the surfing community. | |

| Ch. 9, pp. 130-133, Body Surfng and Bellyboarding | Of

the four

pages devoted to body surfing and bellyboarding, 2.5 pages cover body

surfing and 1.5 pages are on bellyboarding. No section covers hand

boarding or kneeboarding. Key passages include:

|

||

| Overall observation | Although published in 1970, the first edition is mostly written in a mid-1960s flavor with a longboard orientation except in the chapter "The Boards." There are tons of photos but none of bellyboarder/paipo riders. The terms bellyboard and paipo ("as they are called in Hawaii) are both used. In the glossary defines paipo, but not bellyboard, "Paipo: the Hawaiian term for a bellyboard. See Chapter 9." There is no real discussion of board lengths, widths, thickness or plan shapes. | ||

Beginning of Entry xxxx

|

Rodriguez, Rodrigo. (1952). Paipo Forever!. Rincon, PR: 2nd Rock Publishing. |

|||

| Title page and Contents [PDF] and Introductory Chapters Source(s) |

|

This book on surfing for life is written by an older man, especially for the late-1960s era. Allen states, "I am a 41-year-old family man, a respected community member, and a university professor who holds the Ph.D. degree. I am also a confirmed surfer." This is in contrast to the youthful, rebel stereotypes of the era. He goes on to state, "...most older men look upon surfing as either a frivolous waste of time or an activity appropriate only for youngsters - if for anyone at all." He also talks about surfing as a fad, the increasing commercialism of the sport and paradoxically the high degree of conformity within the surfing community. | |

| Ch. 9, pp. 130-133, Body Surfng and Bellyboarding | Of

the four

pages devoted to body surfing and bellyboarding, 2.5 pages cover body

surfing and 1.5 pages are on bellyboarding. No section covers hand

boarding or kneeboarding. Key passages include:

|

||

| Overall observation | Although published in 1970, the first edition is mostly written in a mid-1960s flavor with a longboard orientation except in the chapter "The Boards." There are tons of photos but none of bellyboarder/paipo riders. The terms bellyboard and paipo ("as they are called in Hawaii) are both used. In the glossary defines paipo, but not bellyboard, "Paipo: the Hawaiian term for a bellyboard. See Chapter 9." There is no real discussion of board lengths, widths, thickness or plan shapes. | ||

Beginning of Entry xxxx

|

Rodriguez, Rodrigo. (1952). Paipo Forever!. Rincon, PR: 2nd Rock Publishing. |

|||

| Title page and Contents [PDF] and Introductory Chapters Source(s) |

|

This book on surfing for life is written by an older man, especially for the late-1960s era. Allen states, "I am a 41-year-old family man, a respected community member, and a university professor who holds the Ph.D. degree. I am also a confirmed surfer." This is in contrast to the youthful, rebel stereotypes of the era. He goes on to state, "...most older men look upon surfing as either a frivolous waste of time or an activity appropriate only for youngsters - if for anyone at all." He also talks about surfing as a fad, the increasing commercialism of the sport and paradoxically the high degree of conformity within the surfing community. | |

| Ch. 9, pp. 130-133, Body Surfng and Bellyboarding | Of

the four

pages devoted to body surfing and bellyboarding, 2.5 pages cover body

surfing and 1.5 pages are on bellyboarding. No section covers hand

boarding or kneeboarding. Key passages include:

|

||

| Overall observation | Although published in 1970, the first edition is mostly written in a mid-1960s flavor with a longboard orientation except in the chapter "The Boards." There are tons of photos but none of bellyboarder/paipo riders. The terms bellyboard and paipo ("as they are called in Hawaii) are both used. In the glossary defines paipo, but not bellyboard, "Paipo: the Hawaiian term for a bellyboard. See Chapter 9." There is no real discussion of board lengths, widths, thickness or plan shapes. | ||

|

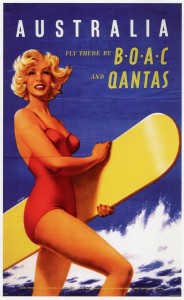

Anthony, Scott, and Oliver Green. 2012. British aviation posters: art, design and flight. Farnham, Surrey: Lund Humphries. |

|||

| p. 135 |

|

Paipo

significance: a poster promoting BOAC and Qantas airlines features a

bathing beauty sporting a bellyboard (also called a surfboard in the

U.K. and Australia before the 1970s). In the on-line article promoting the book there appears to be a slight discrepancy on the date of the poster. Above the poster the article states, "...a 1958 poster depicts a bikini-clad, surfboard-holding blonde below the words “Australia – Fly there by BOAC and Qantas”.Image sourced from the on-line article: Business Traveller. (2012, July 16) BA launches aviation poster book - Business Traveller. Retrieved May 04, 2013, from www.businesstraveller.com/news/ba-launches-aviation-poster-book. The bottom of the poster in the book states, "British Overseas Airways Corporation in Association with Qantas Empire Airways Limited - South African Airways - Tasman Empire Airways Limited" Thanks to Philip Zibin for the article referral. |

|

| Overall observation | A couple of questions about dating of the poster -- 1956 or 1958 -- and the woman is certainly not wearing a bikini! The book cites the poster as c.1956. |

||

|

Aguirre, David. 2007. Waterman's eye: Emil Sigler--surfing San Diego to San Onofre, 1928-1940. San Diego: Tabler and Wood. |

|||

| Cover |

|

This book contains one image with a paipo/bellyboard pictured in the foreground (see below). Photo caption: "A crowded surfing contest at San Onofre in 1938. Five years before this, there had only been a handful of surfers at San Onofre. The Old Mission Beach gang did not compete, but watched carefully to see how the other guys surfed. The San Diegans' boards, which had only 1 inch fins, were not well suited to competition." Click on the photo for a close-up snippet of the board. |

|

| Photo on p. 77 |

|

||

| Overall observation | Unusual photo of an early paipo board, ca. 1938. |

||

|

Allen, Jim Lovic. 1970. Locked in: Surfing for life. South Brunswick: A.S. Barnes. |

|||

| Title page and Contents [PDF] and Introductory Chapters |

|

This book on surfing for life is written by an older man, especially for the late-1960s era. Allen states, "I am a 41-year-old family man, a respected community member, and a university professor who holds the Ph.D. degree. I am also a confirmed surfer." This is in contrast to the youthful, rebel stereotypes of the era. He goes on to state, "...most older men look upon surfing as either a frivolous waste of time or an activity appropriate only for youngsters - if for anyone at all." He also talks about surfing as a fad, the increasing commercialism of the sport and paradoxically the high degree of conformity within the surfing community. | |

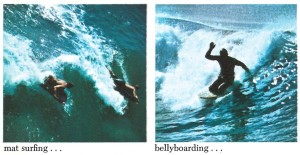

| Ch. 9, pp. 130-133, Body Surfng and Bellyboarding | Of

the four

pages devoted to body surfing and bellyboarding, 2.5 pages cover body

surfing and 1.5 pages are on bellyboarding. No section covers hand

boarding or kneeboarding. Key passages include:

|

||

| Overall observation | Although published in 1970, the first edition is mostly written in a mid-1960s flavor with a longboard orientation except in the chapter "The Boards." There are tons of photos but none of bellyboarder/paipo riders. The terms bellyboard and paipo ("as they are called in Hawaii) are both used. In the glossary defines paipo, but not bellyboard, "Paipo: the Hawaiian term for a bellyboard. See Chapter 9." There is no real discussion of board lengths, widths, thickness or plan shapes. | ||

|

Ash, Dick. 1994. Bellybogger: The fastest way to get your guts across a wave. Byron Bay NSW, Australia: The Author. |

|||

| Short Booklet |  |

A few snippets

from the booklet:I realise that the Bellybogger is not everyone's answer to surfing. But, I believe there's a small group of enthusiasts out there who still know what the art of bellyboarding and bodysurfing is all about.Download and read the 12-page booklet here. [PDF, 3.5MB] |

|

| Overall observation | The Bellybogger inventor and author of the booklet establishes early on that the Bellybogger bellyboard/paipo is not for everyone but that it is the board of choice for many. In the booklet, Dick Ash describes the evolution of the Bellybogger and compares and contrasts it with the boogieboard. He explains how the board has been designed for speed. | ||

|

Bartlett, Vernon, and Maurice Bartlett. 1953. You and Your Surfboard. London: The Author. (With additional illustrations by Maurice Bartlett.) |

|||

| Pages 3 & 4, selected excerpts |  |

Booklet in

PDF: You may download the booklet here.

Note that in the quotes below that there is no reference to stand-up

surfboards. [

|

|

| Editor's Note | The pictured boards appear to be about 50 inches long. It would be interesting to know the length and width of Bartlett's boards and the dimensions of the boards used in Durban, South Africa. | ||

| Overall observation | An enjoyable read. The illustrations and writing are sure to bring a smile to your face as you browse through this book about one's joy in surf riding. The title may be a little misleading since the booklet is about waveriding with a bellyboard (paipo) and not the "surfboard" ridden in the erect style, such as on a longboard or shortboard. This booklet may be the first documented riding of paipos in the far reaches of the world, including the shores of England, Sri Lanka (formerly Ceylon), South Africa (Natal and Cape Town) and West Africa. This booklet was privately printed around 1950, with a couple of editions. Through much diligence over quite a few years a copy was finally acquired by Henry Marfleet (known as "bluey" on the paipo forums). Bluey says, "It was well worth the wait." | ||

|

Beattie, H. 1919. Traditions and legends. Collected from the natives of Murihiku. (Southland, New Zealand) Part XI. Journal of the Polynesian Society, 28(112), 212-225. For access to the article on the Internet click here. |

|||

| Pages 221-222. | SURF-BATHING. At least four of the old men mentioned the sport of surfing, as follows:—“The young Maoris would swim out with a short board, put it under the chest and shoot in on the waves. I remember round at Kakararua (Hunt's Beach, Westland) we were at it, and a white man named Baker would try it. He was a big, heavy man, and when he came in his board struck the shore and almost stunned him. His chest was rather severely hurt.” “The board used in surfing was called a papa, and it requires certain practice to use it. You must keep the end of it up just as you reach the beach or it will dig into the sand and perhaps break your ribs. The board was about four feet long perhaps, and came in like an arrow. I was round at the West Coast diggings, and the beaches there are very suitable for it. Another sport was when the boys would take a tawai (a kind of canoe) out and come in through the surf. They would capsize sometimes but that was all the more fun.” “I never saw the sport of surfing, but know that a papa or surf-board was used. I have heard that in the whaling days old Takata-huruhuru went surfing in the bay at Port Molyneux. He was a descendant of the people who came south in the Makawhiu canoe.” The late Tare te Maiharoa said:—“Take kelp off the rocks and dry it as for pohas or kelp bags [to preserve birds in]. Take two of these bags and tie them together about two feet apart. Blow them up, and having got them out beyond the surf, put one on each side of you from the armpits to the hips, lie on the flax connecting them, and come in with the breakers. It is fine sport and you cannot drown. This was an old pastime at Moeraki, Waikouaiti, and other good beaches, and was called para. (He pronounced it pālă.) In the old Maori days there were very few sharks about—they have only come in any numbers since the European fishermen throw the fish-heads back into the sea.” The names papa and para are interesting. The collector looked up Tregear's Dictionary, and in it he notes that in Hawaii a surf-board is called papa, and in Tahiti it is named papahoro. As for para the nearest appropriate meaning seems to be “the half of a tree which has been split down the middle” (and hence may be cut down into a surf-board) but perhaps Maori scholars could help to explain the term para. |

||

| Overall observation | Two interesting

observations: (1) the Maori rode a form of paipo board, the papa

and (2) a form of surf mat, the para. Methodology question as to when the interview(s) were conducted, the ages of the people, and a specific time reference, per "The question of acquatic sports cropped up in conversation with the old men, and here is what they said... ." on page 221. One person cited on p. 222, Tare te Maiharoa, had recently passed away (see p. 225). When were the whaling days old Takata-huruhuru? |

||

|

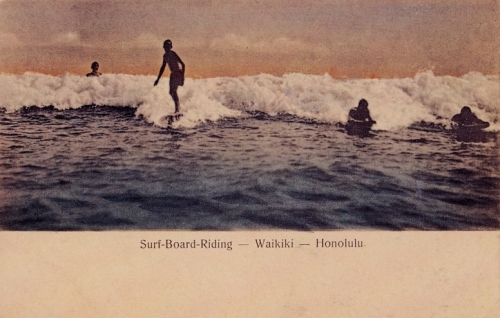

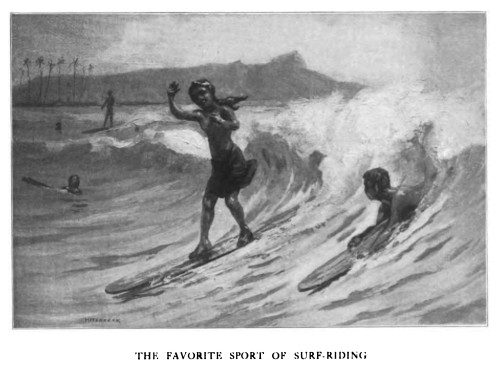

Blackburn, Mark. 2000. Hula girls & surfer boys, 1870-1940. Atglen, PA: Schiffer Publ. |

|||

| Cover and About the book. |

|

About the book: Powerful portrayals of Hula and surfing in the past represent the quintessential Hawaiian experience. Over 270 original photographs and post card images are presented chronologically from 1870 to 1940 to portray the evolving styles and popularity of these icons of Hawai`i. The Hula and surfing traditions both are deeply rooted in legend and myth and Hula dancing was actually outlawed for over 60 years. Surfboards were highly prized by the ancients and the sport became reserved for Hawai`i's kings. These enchanting images include famous personalities including Duke Kahanamoku as well as unknown practitioners of their arts. [inside cover] |

|

Preface / Introduction |

The author's introductory statement on the Hula and surfriding are on pages five and six [text only]. The preface begins, "When you hear the word Hawai`i, one of the first things that comes to mind for most people is the image of Hula girls and Surfer boys. It iswith this concept that this image-driven book has come forth. |

||

|

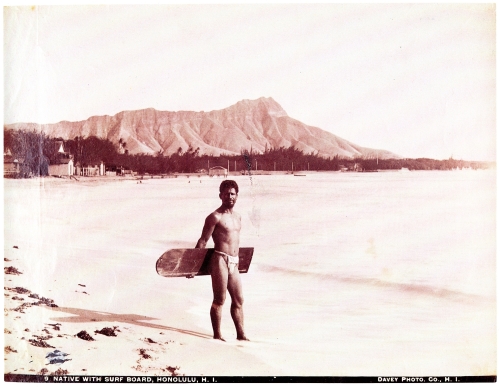

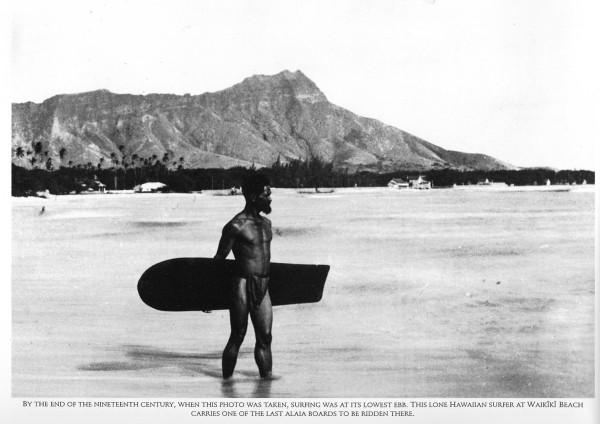

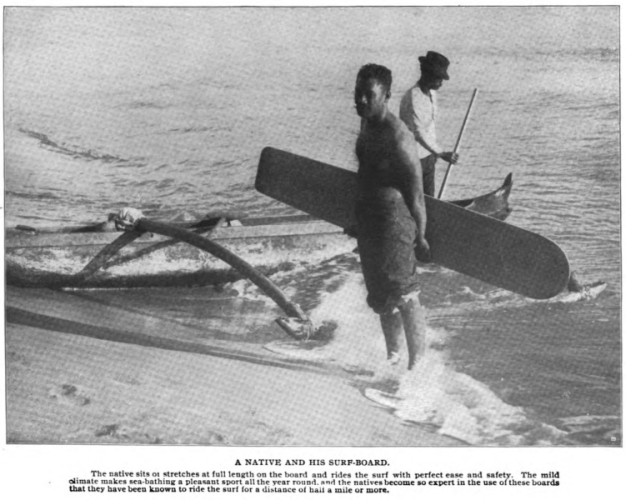

Pictured below is a popular pose of a native holding a surf board with the scenic Diamond Head in the background. This image is of significance in the paipo surfing world because the man is holding a paipo and not an alaia surfing board. The board in this photograph appears to be around 48 inches long with a very parallel planshape compared to the typical board shown in these images that measures at least 5-foot long and is wider overall (especially so in the nose). For example, see the image below from p. 28. Native With Surf Board (p. 9).  The sourcing of this image is: Davey Photo. Co., “9 Native With Surf Board, Honolulu, H.I.,” Hawaiian Historical Society Historical Photograph Collection, accessed July 1, 2013, http://www.huapala.net/items/show/6544. In Timothy Tovar DeLaVega's Surfing in Hawai'i 1778-1930 [p. 32], he notes that London-born Frank Davey, Davey Photo Co., was very prolific, although Davey only documented Hawai`i from 1897 to 1901. |

|||

|

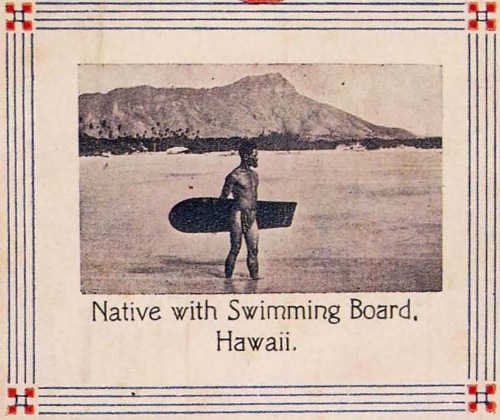

Native holding an Alaia-style surfing board (p. 28).  Snippet from Postcard, "Native with Swimming Board, Hawaii." Copyright 1908 by Franz Huld Company, New York |

|||

|

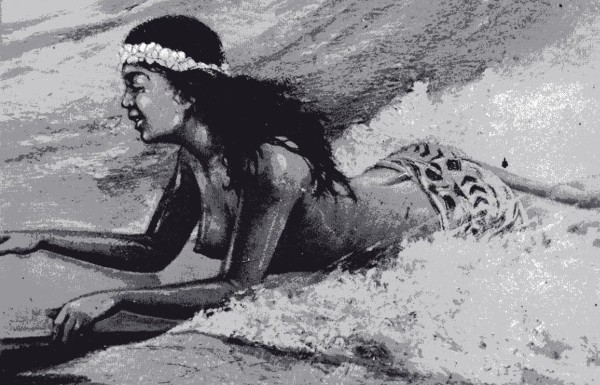

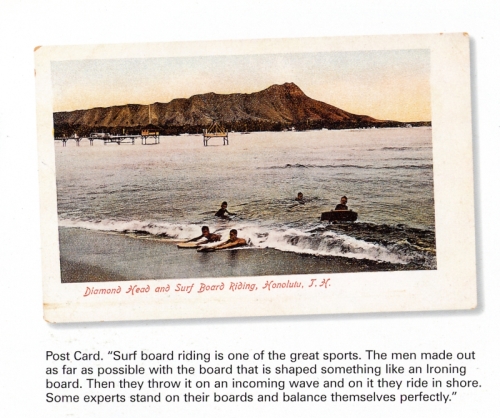

Another common scene showing kids prone riding the waves onto the shore is shown below (p. 36).  Two surfriders riding kipapa-style on their alaia or paipo boards (p. 96).  This post cards appears on the bottom half of p. 96. |

|||

| Overall observation | Hula Girls & Surfer Boys

is rich in photographic and post card history documenting two important

components of Hawai`ian history and culture. Maybe my eyes were not

sufficiently open before but there is a treasure trove of Hula-related

images in this excellent book. The post card image on page 9, is significant in showing a person holding a paipo instead of an alaia surfriding board. |

||

|

Clark, John R. K. 1977. The Beaches of O'ahu. (A Kolowalu book). (Rod's Note: I have not seen the 2005 revised edition.) |

|||

| Page 9, in the

section titled "Paipo Board Surfing" JPG (300KB) PDF (600KB) |

|

Origins of a

word: The first paragraph reads: "In the days of old, Hawaiians

referred to bodysurfing as kaha (or kaha nalu) and pae

(or paepo`o). During the early 1900s, the term paepo`o

was commonly used in Waikiki, and it meant riding a wave with only the

body. After World War II, this particular word took on an alternate

definition, referring to bodysurfing with a small board. The

pronunciation of the original word, paepo`o,

was altered, and now even the spelling is changed to paipo. Today "to

paipo" means to go bodysurfing with a "bellyboard." The board itself is

called a paipo board." The second paragraph describes paipos and paipo riding: "Paipo board surfing is an intermediate development between bodysurfing and surfboard riding. The paipo board is small (3 to 4 feet long), thin (about 1/4 inch thick), and usually made of plywood that is protected by paint or some other waterproofing. The shapes and sizes vary according to individual preferences. Because paipos usually are ridden in a prone position, some spectators call them "bellyboards." The paipo board rider has much more speed and freedom of movement than does a bodysurfer and often catches much longer rides. |

|

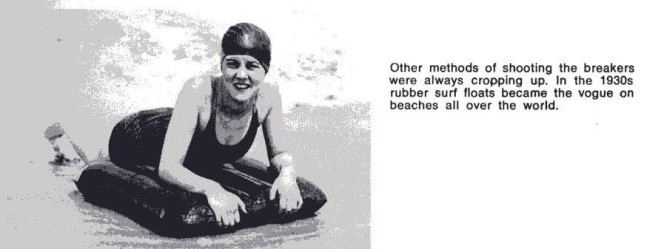

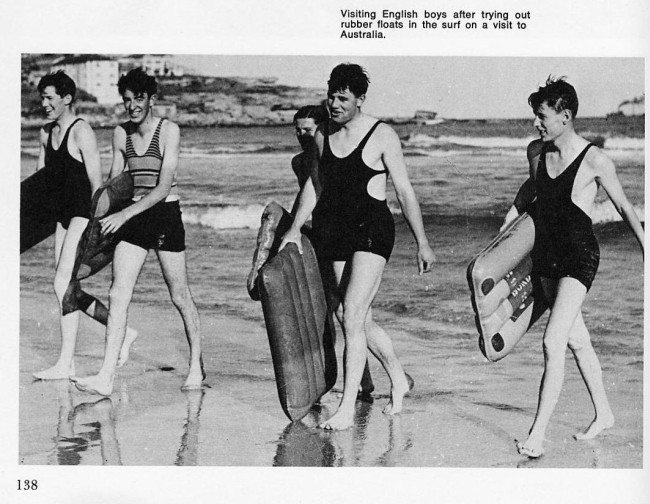

| Some paipo riders

prefer to kneel on their boards, a technique that reduces their speed

but allows them maximum maneuverability in the critical sections of the

wave. The big outside breaks at Makapu`u attract some of the best paipo

riders on O'ahu, and it is well worth the drive to watch them perform

on a good day." The third paragraph describes mat surfing: "A variation of paipo board riding is "mat surfing." Instead of a board, the rider surfs on a small, air-filled, canvas mattress. However, several shortcomings have kept mat surfing from gaining widespread popularity. The mats are very buoyant, which makes them hard to take out through incoming surf; they are reluctant to go in any direction other than straight toward shore; and finally, they deflate when punctured. In spite of these drawbacks, mat surfing still remains a very enjoyable sport." |

|||

| Overall observation | |||

|

Clark, John R. K. 2002. Hawaiʻi Place Names: Shores, Beaches, and Surf Sites. Honolulu: University of Hawaiʻi Press. |

|||

| Page 302 from the story about the beach named Pololū |  |

Origins of a word: The term "paipo" may be derived from the clandestine Hawaiian word, paepō, as told in the following mo‘olelo (or, story) by Alfred Solomon to John Clark: "I was born on September 15, 1905, and I'm a cousin of Bill Sproat... I have two papa paepō in my artifact collection. They're two small concave boards about 1/4-inch by 1 foot by 3 feet made of wiliwili, and they were used for spying. The spies selected a night with rough seas and then surfed in to gather information about various activities. The boards were easily concealed. I heard this from the old people and they said that's why the boards were called paepō, "night landing." - Alfred Solomon, June 25, 1982 | |

| Overall observation | John Clark does a wonderful job documenting and describing the names and uses of beaches in the Hawaiian islands by interviewing people who lived and used them. One of his styles of interviewing is through the collection of stories (mo‘olelo) of a beach. As Clark states in the preface, "One of the important rules about place names in the Hawaiian language is that you never know the true meaning of a name unless you know the mo‘olelo, or story, that goes with it." | ||

|

Clark, John R. K. 2011. Hawaiian Surfing: Traditions From the Past. Honolulu: University of Hawaiʻi Press. |

|||

| TBD. See Wally Froiseth paipo

board logo. |

|

See the New York Times op-ed article here. Lawrence

Downes. (2011, July 7). Big Boards, Banana Stalks and Everybody in the Waves [book review of "Hawaiian Surfing: Traditions from the Past" and "Waves of Resistance: Surfing and History in Twentieth-Century Hawaii"]. The New York Times, p. A22. Retrieved July 11, 2011, from http://www.nytimes.com/2011/07/08/opinion/08fri4.html Origins of a word: John Clark's forthcoming book identifies and describes the types of surfing that native Hawaiians did, one of which was pae po'o, or prone board riding. He notes that while it's true that "paepo" can be translated as "night landing" (as noted in the mo‘olelo by Alfred Solomon), Clark has since learned that the original word was actually "pae po'o". The following is from the manuscript: "In the earliest descriptions of surfboards by Hawaiian scholars, the smallest boards, those that were shorter than six feet in length, were generically called papa li`ili`i, or "small boards." During the early 1900s, the name papa li`ili`i was changed on two fronts with non-Hawaiian surfers calling them bellyboards, because they were most often ridden prone, the rider laying on his or her "belly," and with Hawaiian surfers in Waikiki calling them pae po`o boards. |

|

| Pae po`o is an interesting word. It does not appear

in any Hawaiian dictionaries, Hawaiian language newspapers, or writings

of the prominent Hawaiian scholars of the 1800s, such as `I`i, Kamakau,

Kepelino, and Malo, who described traditional Hawaiian surf sports. The

term appears to have been coined by Hawaiian surfers in Waikiki circa

1900, where it was commonly used to mean bodysurfing or bodysurfing

with a small wooden bodyboard. The literal translation of pae po`o

is "ride [a wave] head-first", or in other words, bodysurf, and a papa

pae po`o was a bodysurfing board, or what surfers today call a

bodyboard. In everyday conversation, pae po`o was often shortened to pae po, which is common among Hawaiian words that end with double "o's," such as Napo`opo`o on the island of Hawai`i, which is often pronounced Napopo. The popular spelling used today, paipo, was coined by Hawaiian surfing legend Wally Froiseth, who, besides being an excellent surfer, was an exceptional paipo board rider who was famous for standing on his twin-fin board while riding big waves. From 1956 to 1986, Froiseth made approximately 150 paipo boards, which he sold to friends and other surfers, putting a decal on each board to identify it as his product. No one before him, however, had ever spelled pae po, so without the benefit of seeing the word in print, Froiseth spelled it as he heard it, pai po. His decals read, "Hawaiian Pai Po Board. Mfg. by Froiseth." Froiseth sold some of his boards to surfers from California, which helped to introduce the word and its spelling outside of Hawai`i, and today paipo is the accepted term for wooden bodyboards." |

|||

| Overall observation | Historic documentation for the word, paipo. | ||

|

Cralle, Trevor. 2001. The Surfin'ary: A Dictionary of Surfing Terms and Surfspeak. Berkeley, CA: Ten Speed Press. (2nd Ed.) |

|||||

| Road Map to Sources |  |

|

|||

| Definitions | Listed below are

several of the terms related to prone riding that are listed in The

Surfin'ary: alaia board n. An ancient Hawaiian board for bodysurfing. (DM) belly board or belly board n. A small surfboard used primarily to ride the waves on your stomach, but It can also be ridden kneeling or standing. (MF) Same as PAIPO BOARD. bellyboarding n. Bodysurfing with the aid of a planing device, such as a small hand-held kickboard or surfboard. bodyboard n. Originally a BOOGIE BOARD, but now includes soft foam boards with a hard plastic or fiberglass covering. bodyboarder n. Someone who surfs using a bodyboard. bodyboarding n. Riding a bodyboard in the surf. Bodyboarders originally rode lying down, but now they occasionally stand up. See BOOGIE BOARD. bodysurfer n. 1) A surfer who rides the waves with the body alone; swim fins are sometimes used to help propel the bodysurfer through the wave. 2) Someone who uses the body as a wave vehicle. bodysurfing or body surfing or body-surfing n. The art of riding the waves without a surfboard, using the body as a planing surface. Side caption on page 51: Bodysurfing is considered by some to be the purest form of surfing. The sport was invented by marine mammals such as dolphins, seals and sea lions. Unlike their marine counterparts, however, humans occasionally need to wear swim fins to help them generate enough speed to catch a wave. boogie board n. A soft, flexible foam bodyboard, which can be used in flagged areas. (MW) The original Boogie Board (a brand name) was invented by Tom Morey in 1971. The most widely used surf riding implememt of all time, ridden prone and with or without swim fins. Coolite n. 1) An Australian brand-name for a Styrofoam trainee surfboard. (MW) 2) The first board of most Australian grommets, including MR, Rabbit, and Barton Lynch. (SFG, 1989)

kneeboard n. A surfboard, usually short (fIve to six feet In length), ridden on the knees. (NAT, 1985) kneeboarder n. A surfer who rides a kneeboard. kneeboarding n. Surfing on the knees on a specialized board. The rider can maintain a compact and stable position, good for quick, radical maneuvers, and tube riding. lay down surfing n. BODYBOARDING Lilo (lie-low) n. Australian brand name for an inflatable vinyl SURF MAT. No Aussie ever talks about a raft. McDonald's tray n. Cafeteria-type plastic tray used for bodysurfing planing aide. First used by Hawaiians in Waikiki and now used by many a surfer around the world. On Oahu, frequent "borrowIng" of these trays caused the fast-food restaurants to drill holes into them. Morey Boogie n. The original Boogie Board invented by Tom Morey in the 1970s; developed from aircraft foam. See BODYBOARD, BOOGIE BOARD. paipo, paipo board (PAY-po) n. A small polyurethane-foam bellyboard used in the Hawaiian Islands. skimboard or skim board n. A rounded plywood or fiberglass board two or three feet across, used to slide over the shallow water at the water's edge. skimboarding, skimming n. Standing up on a flat board and riding it along the shoreline on top of a thin layer of water. Also called SANDSLIDING. skitter board n. 1) A fast, finless, flat-bottomed bellyboard or paipo board about farly-two Inches long and thirty inches wide and around three-eighths of an inch thick--one of the fastest wave-riding devices. 2) An old term for SKIMBOARD. surf-o-plan n. [Note: I neglected to copy this one down.] |

||||

| Ancient Hawaiian Terms (PDF, 360KB) | The Surfin'ary provides a good, concise collection of ancient Hawaiian surfing terms terms. The list relies heavily on secondary sources, such as the listing of terms in the excellent Ben Finney and James D. Houston book, Surfing--The Sport of Hawaiian Kings, and the lexicon in the Gary Fairmont R. Filosa II book, "The Surfer's Almanac: An International Surfing Guide." The list of terms relies less on a close review of original source material such as the seminal dictionary by Lorrin Andrews, "A Dictionary of the Hawaiian Language To Which Is Appended an English-Hawaiian Vocabulary and a Chronological Table of Remarkable Events [1865]." For example, conspicously missing from this listing are two terms, pae (to be carried along by the surf towards the shore; to play on the surf-board) and aupapa (losing one's board, or "wipe-out"). Nonetheless, this is probably one of the best consolidated listings of ancient Hawaiian surfing terms one will readily find. | ||||

| Overall observation | My

optimism on the overall potential of this book disappeared as I read

and browsed through it. Some of the definitions related to prone

surfing are almost hilarious, but upon a second glance would simply benefit

from a refreshing update. The book appears to be heavily influenced by

the author/editor's California and "pure, stand-up" roots. For example,

this passage from early in the book, "What is Surfing?""Surfing is a thrilling water sport for persons of all ages thaI has been practiced for centuries. The act itself involves riding across the face of a wave toward the shore while standing on a special board, called a surfboard. Modern surfboards are made of foam and fiberglass and come in various shapes and sizes, from short boards to longboards and everything in between.A close attention to the ancient history of surfing reveals a rich history of bodysurfing and board riding prone, kneeling, and sitting, in addition to standing. There is nothing "pure" about riding a board in the stand-up position. It also strikes me as peculiar, or even naive, to call a kneeboard a "specialized surfboard." There are probably about twenty derogatory terms for bodyboarding sprinkled throughout the dictionary plus a special section in the appendix, but there is no such attention to detail for "stand-up statue riders." Nonetheless, there are several highlights sprinkled throughout. Note: I have not reviewed the first edition. |

||||

|

DeLaVega, Timothy Tovar. 2011. Surfing in Hawai'i 1778-1930. Arcadia Pub. |

|||

| Title page and Contents and Acknowledg- ments [PDF] |

|

The

publisher describes the book, "In this volume, Kauai resident and surf

historian Timothy DeLaVega has orchestrated a worldwide team of surfing

historians, who have compiled surfing images that span the centuries

from ancient petroglyphs (rock etchings) to the first modern surfing

boom at Waikiki. These images offer a unique and historical

perspective, with many never-before-seen images of surfing in Hawai'i." In the acknowledgments, DeLaVega states, "This project was done to properly identify the early photographers/artists as well as establish a proper timeline of early surfing images. We hope you enjoy our discoveries and that this will promote future research. This book could never have been accomplished without a worldwide TEAM (Together Everyone Achieves More) of dedicated surfing fanatics who have again combined energy to create our third project in 10 years. This book is an example of aloha (affection, love, and peace), as each door I knocked on was opened wide with warmth and love." |

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|||

| Overall observation | Since John Clark's recent publication, Hawaiian Surfing: Traditions From

the Past (2011), this is the first book, to my knowledge, to use the term papa li`ili`i, the origins of the

word, paipo. DeLaVega does a fine job once again in putting together a book intended for people with an appreciation of wave riding history and traditions, and a love for he`e nalu (wave sliding). A solid addition to any collection of surfing books. |

||

|

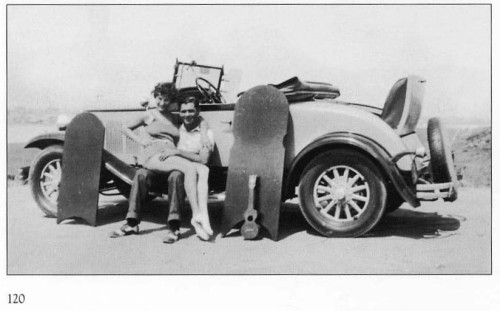

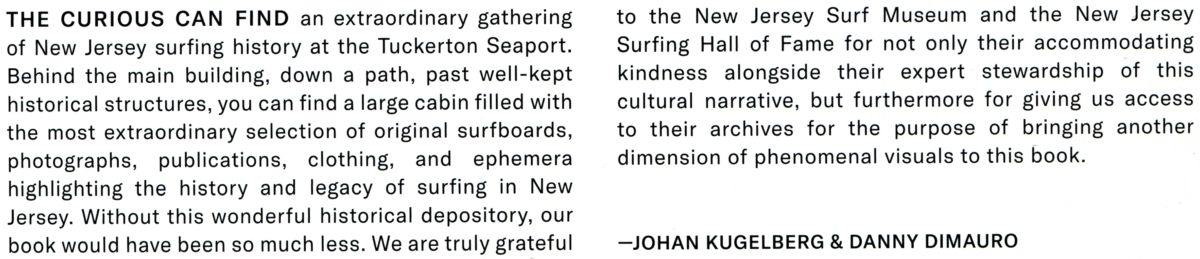

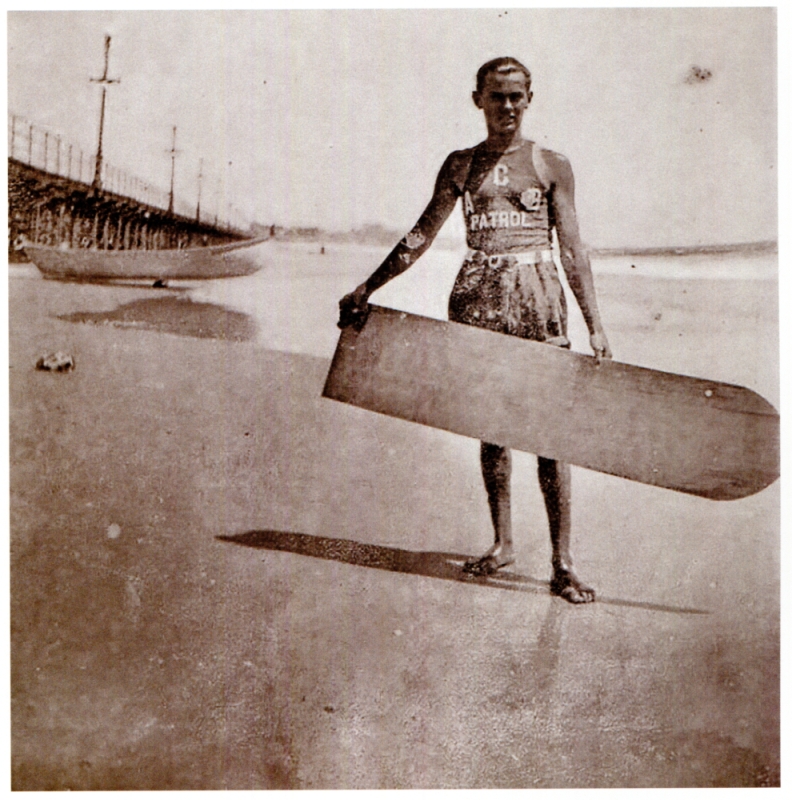

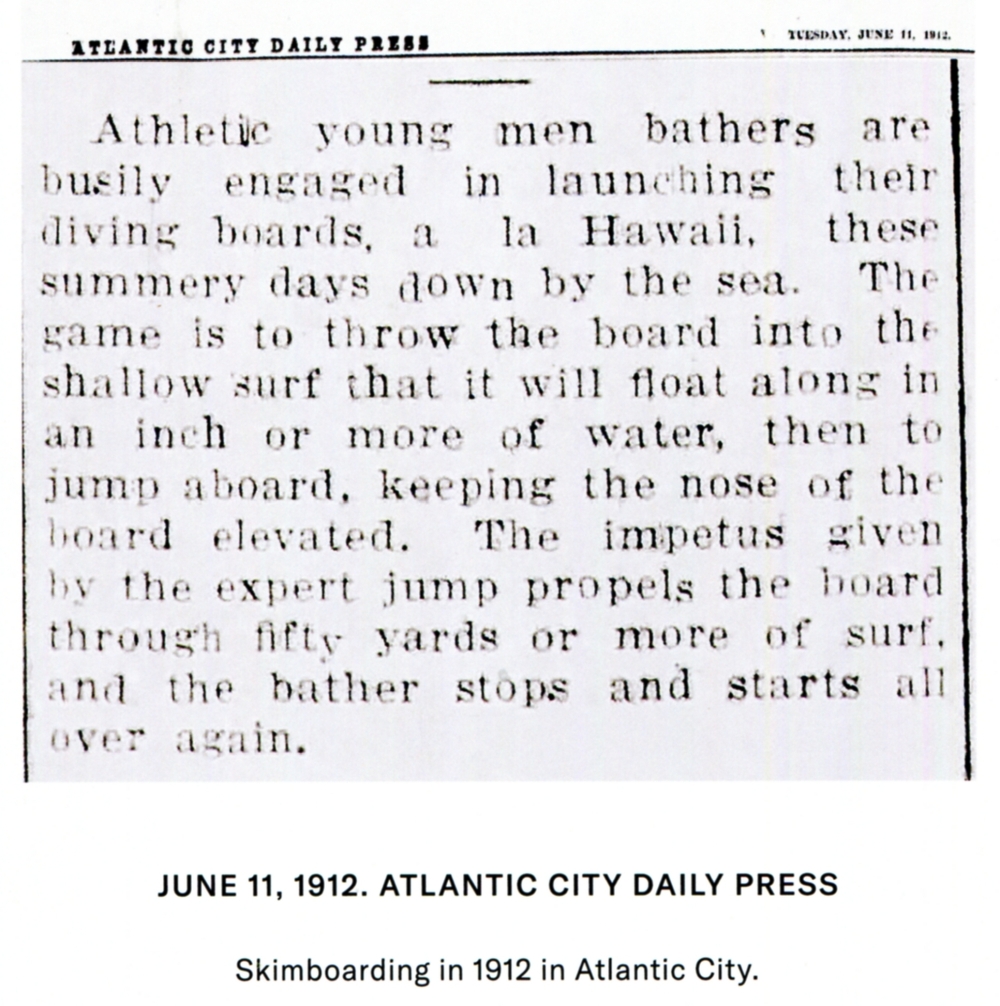

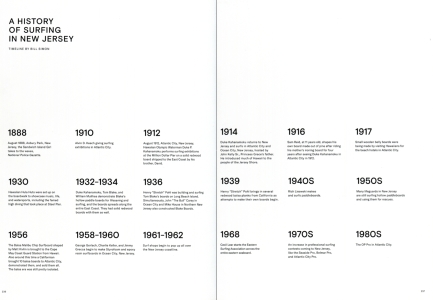

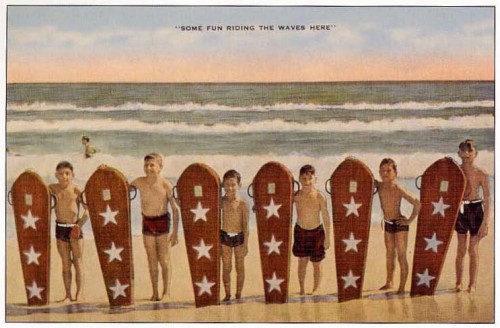

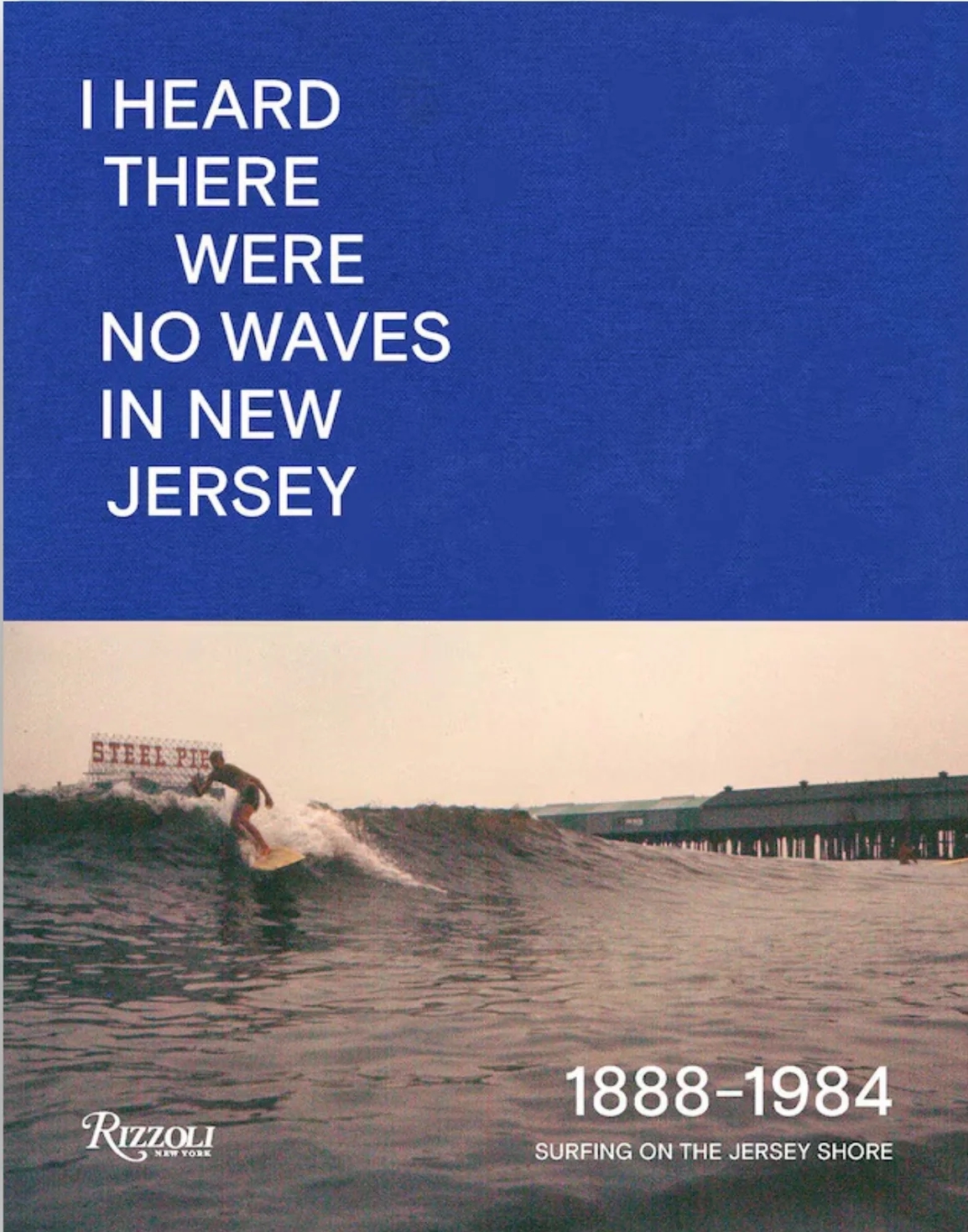

DiMauro, Danny, and Johan Kugelberg. 2024. I Heard There Were No Waves in New Jersey : Surfing on the Jersey Shore 1888-1984. New York: Rizzoli International Publications. |

|||||||

| Cover, Title page and Contents and inital book sections |

|

This

is a large format coffee table book full of photographs reflecting New

Jersey surf culture from the late-19th century through the 1980s–about 100 years. Most pages feature a single figure or a

two-page spread of a single figure with a small descriptive caption.

There are many nice beach crowd, surfing contest and bikini shots

although the authors are diligent in representing women's role

throughout New Jersey's surfriding history (after all the first surfing

of New Jersey's waves was done by the Sandwich Island Girl (the former name of the Hawaiian Islands. A short article in the book by surf historian, Mike May, outlines some historical waveriding milestones:

|

|||||

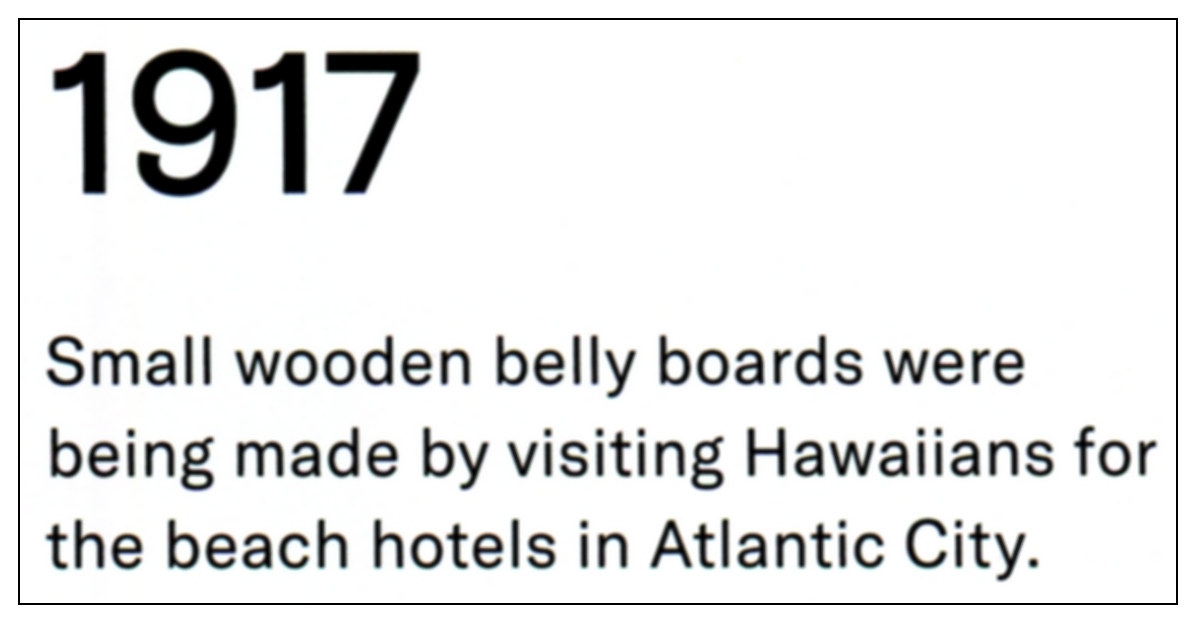

| Section: Beneath the Surfing Underdog, written by ed. Johan Kugelberg. |

One intriguing

historical fact on paipo/bellyboarding in New Jersey emerges in this

solemn litany of New Jersy as underdog surfriding:"By 1917, visiting Hawaiians had constructed wooden belly boards that were in use at several Atlantic City beach hotels." [p. 137]Kugelberg summarizes in the last paragraph of the one-page narrative section, "When Danny and I started working on this project, we were truly lucky to find these caches of unseen masterful photography, and to have been steered in the direction of treasure troves of cultural remains. This book is steeped in romanticism and the picturesque, certainly: the stuff is so cool and visual, and the photography is like stepping inside a gentler time with better clothes. But more than that, I hope this book is a useful stepping stone toward the unveiling of more and more historical and cultural narratives."My appetite was whetted by the above statement in expectation that several historical photographs would emerge. Alas, the following 20+ pages were mostly of 1964 longboarding. Nonetheless, there is promise in learning more about the 1917 bellyboard revolution in Atlantic City! |

||||||

| Section: Ephemera. This section compiled and written by editors Johan Kugelberg & Danny Dimauro. |

|

||||||

| Section: A History of Surfing in New Jersey (pp. 236-7) |

|

||||||

| Overall observation | Not much documentary information on paipo/bellyboard surfing except for some lines in passing. This "surf history in fine pictures" focuses mostly on vertical stand-up surfriding but there are a couple of photos of wave ski surfing and one photograph of an alaia or paipo board. The narrative does mentions raft/mat surfing and skim boarding and boogie/bodyboarding, including on an ironing board. I do not recall a written or visual mention of kneeboarding. Several interesting leads to follow-up on. | ||||||

|

Dixon, Peter L. 1965. The Complete Book of Surfing. New York: Coward-McCann. Dixon, Peter L. 1967. The Complete Book of Surfing. New York: Coward-McCann. (2nd Ed.) |

|||

| Cover, Note

& Contents. Ch. 1, The History of Surfing |

|

Just for

the record. Click here for

the Table of

Contents, (100KB, PDF). Chapter 1, The History of Surfing

|

|

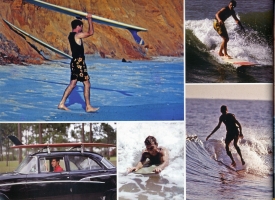

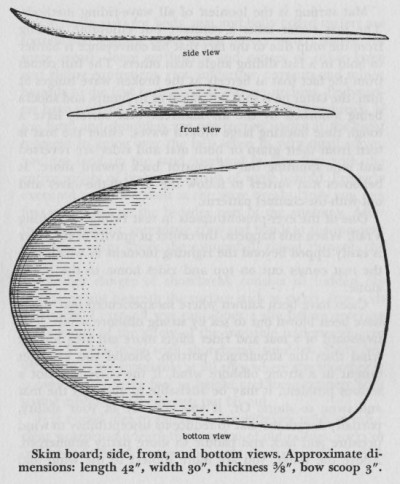

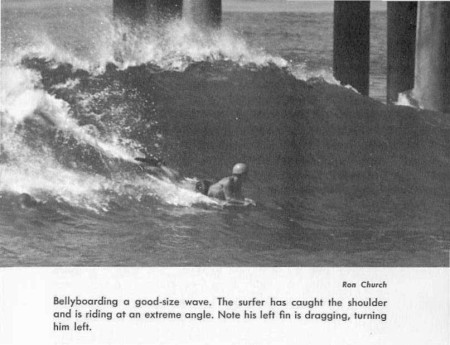

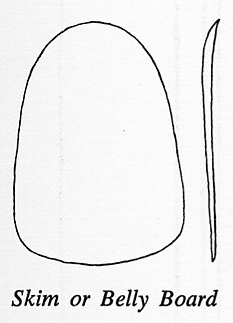

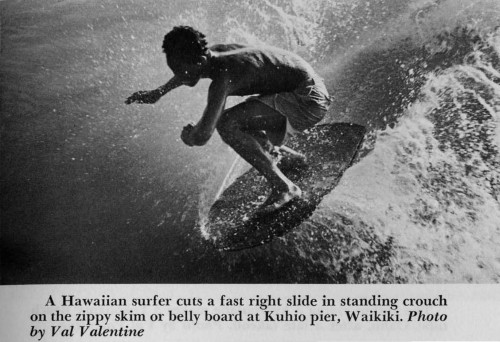

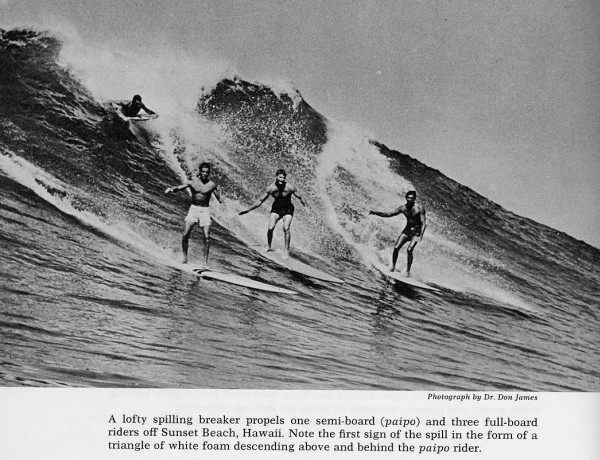

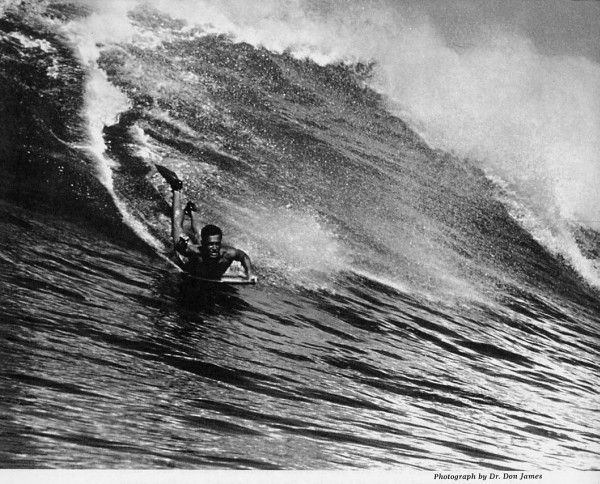

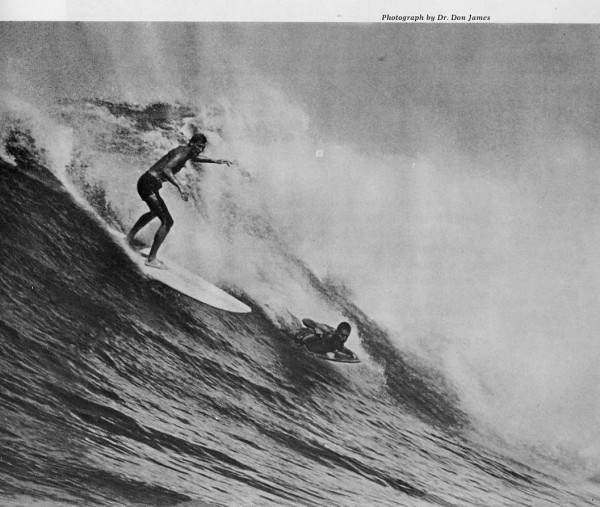

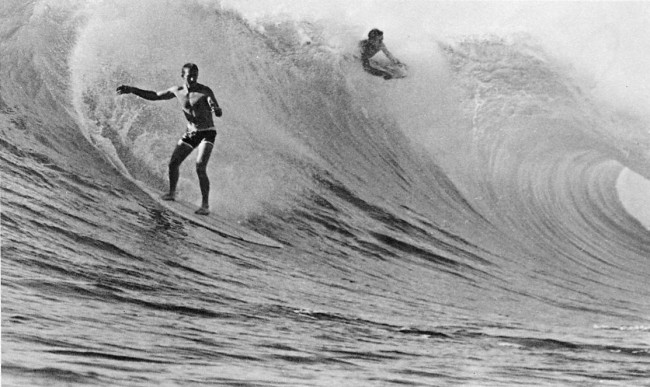

| From Chapter 11, Surf mats, Bellyboards, and Dories (800KB, PDF) | Paragraph

two reads, "Bellyboards are really

little surfboards. Several types are now in use--some are simply flat

pieces of wood with a rounded nose and others have one or two skegs.

The modern commercially made bellyboard is like a full-size surfboard,

except the dimensions have been scaled down. Both mats and bellyboards

are propelled with swim fins on feet and arms paddling." (See the mat surfing pictures from p. 137.) "The Bellyboard" section of the chapter begins on page 139, "The bellyboard is really just a short surfboard. Years ago bellyboards were short wooden planks with rounded ends. Surfers made the start while standing on the bottom and always rode the bellyboard in the white water. The modern bellyboard has grown a skeg, a covering of fiberglass and an inner core of foam. These are very fast, and on the right wave they can go faster than a surfboard. In Hawaii the bellyboards are called paipos and are ridden right along with surfboards, even in the big surf at Sunset Beach." Note the comment in paragraph two, "On medium-size, well-formed waves the little boards are ideal; in fact they're almost as much fun as riding a conventional surfboard." [Editor's Note: Also as fun???]  Picture on page 141. |

||

| Glossary (260KB) |

|

||

| Overall observation | The

book is written in a "popular-style" for a wide audience that covers

many of the bases for introducing standup surfing and other various

forms of waveriding, in particular mat surfing and dory surfing. The

2nd edition uses the terms bellyboard and refers to the Hawaiin name, paipo

board. The 1st edition appears to be virtually the same as the 2nd edtition. No material to add or change. |

||

|

Dixon, Peter L. 1966. Men and waves; a treasury of surfing. New York: Coward-McCann. |

|||

| Cover & Contents. |  |

Overall

observation. An excellent compendium of exceprts from surf-related

publications by several well known authors including James Michener,

Jack London, Tom Blake and Willard Bascom. In the introduction, Peter

Dixon writes, "This book, then, is a colorful collection of man's

relations with the surf as written and photographed by surfers and

those splashed by the waves' spray. The profesSional writers have

alsobeen inspired by the spectacle and experience of surfing." This book about surfing is divided into five sections: 1) the history; 2) the science of sea, waves, and beaches; 3) stories of the people who surf; 4) the adventures of man against the waves; and in the center section, 5) the photographs. |

|

| The book is a good read but unfortunately is light on other forms of waveriding, including bodysurfing, paipo boarding and kneeboarding (and others). There is one picture of a bodysurfer and no mention of paipo or bellyboarding. The book includess a citations page, but no other bibliography or index. | |||

|

Dixon, Peter L. 2001. The complete guide to surfing. Guilford, Conn: Lyons Press. |

|||||

| Title page and Contents |

|

Excerpt from the book description on WorldCat:"This comprehensive how-to book explains the technique, etiquette, and secrets of surfing to any wave rider, be he absolute beginner or seasoned pro. Written by a fifty-year veteran, it first takes the reader step-by-step through such basics as paddling out and judging waves, and goes on to explore such topics as surf-board design, surfing hazards, and radical surfing. Additional chapters survey the world's best surfing areas, examine new sports such as body surfing and surfing Boogie Boards, and even supply tips on how to build your own board."Illustrated with more than 150 color photographs and illustrations. In Chapter 1, "Surfing 's Rich Legacy," the author writes on page 6: "Longer, better-riding boards and the best surfing breaks were reserved for members of the ruling class, the alii. These long boards, called olos, could reach 16 feet and weigh as much as 150 pounds. Commoners used shorter boards, called akaias, which were about eight feet long. Children surfed little planks called paipos, similar to today's bodyboards." [Note: The alaia is misspelled as akaia. Paipos were widely surfed by all ages and genders, not just children]. |

|||

| Ch. 9, pp. 166-175, "Bodyboarding" |

"Many of us who began bodyboarding some years back still call them Boogie Boards. I use the term "boogie" interchangeably with "bodyboard," to refer to the same small and simple, ride-on-your-chest, all-time fun, wave-surfing machine. Bodyboarders are also called "spongers," and the board itself, a "sponge." A skilled bodyboarder on a soft, three- to five-foot-Iong, five-pound boogie, helped along by swim fins, can perform almost every surfing maneuver--and a few more beyond the ability of stand-up surfers." p. 168.Subchapter, "Bodyboards, Past and Present," pp. 169-170: "Before today's flexible foam bodyboard became universally adopted in the late 1970s, there were several variations of these short, prone- or knee-riding surfboards. Bodyboards have always had three major advantages over traditional surfboards: They're easy to learn to ride, they cost much less than surfboards, and they're much more portable."The remainder of the chapter discusses the invention of the boogie board by Tom Morey, the board's general shape and contour, its widespread availability and accesories and equipment used in riding the "bodyboard." A subchapter of general interest is "Boogie Board Swim Fins," part of which states: "Bodyboarders use the same type fins as bodysurfers (see a discussion on fins on page 153 in chapter 8). Since bodyboarders seem to enjoy the more technical side of the sport, several variations of the classic swim fin have been developed and marketed. You'll have a choice of the traditional Churchills, Viper Duckfoots, the Redley fins favored by competitive bodyboarders, and an evolution of the Churchill called a"Slasherfin." Prices range from $35 to $ 75 a pair." pp.174-5. [Note: According to Fred Simpson, founder and owner of Viper Swimfins, there were never a "Viper Duckfoot." Duckfeet were marketed by Voit. It is a stretch to state Redley fins were favored by competitive bodyboarders.]In the next subchapter, "Let's Boogie," the author is spot on in his description of bodyboarding (and paipo/bellyboarding): "Once you've learned the basics, it's easy to catch waves with a bodyboard. Riding a Boogie provides a great workout that's truly fun. And, when the lifeguards raise the black ball flag (no surfing), bodyboarders can keep on riding." p. 175. [Note: Riding kipapa-style is a great workout that's truly fun!] |

||||

| Glossary | The

glossary is a bit more extensive with several "boogie board" related

terms. The definition for paipo remains virtually the same but no

longer included is the term "bellyboard."

|

||||

| Overall observation | This book is largely an updated, modernized version of The Complete Book of Surfing

(first and second editions, 1965 and 1967, respectively), including

numerous color photographs of shortboarding and more photographs of surf

breaks from around the world. The book has several chapters that appear

in the earlier books that cover everything from "how to surf" to safety

and equipment. There is no bibliography or use of footnotes but sources

are incorporated in the text in some places. The book includes a glossary of

surfing terms and an index. This 2001 edition replaces the 1960s chapter title of "Surf mats, Bellyboards, and Dories" with a streamlined "Bodyboarding," which covers early bodyboarding (paipos), boogie boarding and mat surfing. The chapter includes several very good bodyboarding color photographs but no photos of paipos or bellyboards. I was a bit disappointed in the inaccuracy of some of the information. Missed not reading a reference of surfing by Mark Twain (for example, see Twain, Mark. 1872. Roughing It, Part 8, Chapter LXXIII, "Surf Bathing." Hartford, Conn.: American Publishing Co.). |

||||

|

Dixon, Peter L. 2001. Men who ride mountains: Incredible true tales of legendary surfers. Guilford, Conn: Lyons Press. (see first edition [1969] note below. |

|||

| Cover & Contents. Short excerpts. Ch. 8, The History of Surfing |

|

Ch. 8, The

Aussies, and Ch. 10, The Competitors,

are two short acknowledgments of George Greenough's impact on the world

of waveriding. There are several references to Greenough's belly board,

but I suspect this is a kneeboard - no mention is made of Greenough

belly riding or knee riding. For example, on page 121, "The Aussies

couldn't fathom George at first. They were expecting some sort of cool

American cat, polished and citified, which George is not. They were

also troubled by the fact that George didn't ride a surfboard, but only

his radical, self-designed fiberglass belly boards." Later on page 164,

Skip Frye is quoted saying, "Then Greenough came back from Australia

with his mind blown free of all preconceptions and he started a lot of

us looking in new directions. Greenough stressed surfing on anything

people could ride - mats, belly boards, boats, anything that could

capture a wave and slide fast. George designs surfingvehicles. It's as

simple as that." See the excepts here [PDF file]. |

|

| Overall observation | Excellent book on surfing from the early modern years through

the shortboard revolution of the late-60s with other selective updating

of the original 1969 edition, in this 2001 new edition. Well worth the

read for general wave riding history, but very little on the prone

riding world of surfing except the references to "belly boarding" above. Note: Bob Green, Paipo Research Project, reviewed the first edition (1969) and did not see any references to paipo or bellyboarding. |

||

|

Echegaray Eizaguirre, Lázaro, and Mikel Troitiño Berasategi. 2007. What the waves brought in: a history of surfing in Zarautz. Zarautz: Ayuntamiento de Zarautz, Departamento de Cultura. [Also published in Spanish and Basque -- see the Paipo Bibliography.] |

|||

| Title page and Contents [PDF] and Introductory Chapters Source(s) |

Cover page goes here. | This

book documents the origins of surfing in Zarautz, a coastal town

located in the province of Gipuzkoa, in the Basque Country, northern

Spain. In it is a chapter on "bodyboarding." The first chapter

summarizes the beginning of bodyboarding in this area:"The bodyboard came to Zarautz by way of a local carpenter, Marcelo Linazasoro, in the early 1950's. He had seen them on the French coast, at the Cote des Basques, in Biarritz, and he thought it would be a good idea to make some in Zarautz and rent them out on the beach next to the canoes. The French called it bodysurf, and some theories believe that this was the first form of surfing to reach Europe. It was used to catch waves lying down on top of the thing. It was a piece of wood that looked like an ironing board, but shorter, wider and slightly raised at the nose. For a long time, this was one of the most outstanding activities at the beach, competing with the "aspirin," also made of wood and similar to the bodyboard, but completely flat, rounder, and used to skim across the fine layer of water left on the shore after the wave retreated." [p.21]Eventually, swin fins enable more varied surfriding: "At the beginning ofthe 70's, kids started wearing swim fins and looking for the peak. Before this time, they would normally ride the white water onto shore. The swim fins allowed for them to catch the bigger waves."The sport of waveriding prone and the boards continued to evolve: "The kids would paint thelll with their favourite colors and designs, they would put fins and leashes on them, which were basically a piece of rope wrapped in plastic and with a wristband at the end. They even tried putting cork plaques onthe bottom so they would float more."The four-page chapter contained several interesting photographs of the materials used to form the bodyboard, or txampero in Basque (see a couple of sample figures below). |

|

| Chapter on Bodyboarding, pp. 20-23 |

Homemade bodyboard press   Source: pages 20 and 23. |

||

| Overall observation | Local paipo boarding began after watching surfing on similar planks in southern France. I did not review the book in its entirety so do not know to what extent other forms of prone surfriding craft were included. The English version in this chapter did not use the term txampero that was used in our interviews with area surfriders (e.g., see Green, Bob. (2011, September 20). A Paipo Interview with Javier Arteche: El Txampero in Spain. Accessed at MyPaipoBoards.org, February 13, 2012. |

||

|

Ellam, Patrick. 1956. The sportsman's guide to the Caribbean. New York: Barnes. |

|||

| Forward Chapter 2 section on surfing. |

|

In the Forward

the author notes, "The aim of this book is to give an accurate account

of the sporting facilities that are available throughout the islands of

the Caribbean; to show where they are, what they are like, who runs

them and what equipment they have." Chapter 2, Participation Sports, in the section titled "Surf Riding," the following: SURF RIDING Where to go: There is only one place where the surf riding is good and that is at Trinidad. They have a good beach facing directly into the Trade Winds with either side of it a headland running well out to sea, forming a deep V-shaped bay. In the middle of the bay the Atlantic rollers pile up on a series of sand bars and travel for some distance before they break, providing just the right conditions for a good ride. No instructors are available, but it is quite easy to learn on your own and once you get the hang of it you will find it a safe, pleasant and rather romantic sport that somehow fulfils the dreams one has on cold winter nights of far-away tropic islands. |

|

| The beach: It is called Maraccas Bay

and lies on the North shore of the island about 14 miles from Port of

Spain. To get there you either rent a car or take ataxi, making a deal with the driver for the

round trip before you start. But first you call at a timber yard in town and get them to make you a board each. They use the short type there so that all you need is a 4-foot length of cedar or similar wood about 15 inches wide, not too heavy and rounded off at one end (the front). Any yard will make them for you in a few minutes while you wait and the usual charge is about 60 cents each, but make sure that they do not leave any rough edges or splinters. The road from town climbs up over the mountains and drops sharply down on the other side, providing one of the most scenic drives in the whole Caribbean, while Maraccas Bay itself is strictly glamorous, with the sweeping curve of white beach and the high green headlands stretching away on either side. On weekends there will be a line of cars parked under the palm trees and everyone from town will be out there but at other times it is quiet, with just a few other people around. Using a surf board the trick is to get started. In the beginning it is best to wade out to the first sand bar, where the water is no more than waist deep, face the beach and wait for a wave that is just about to break as it reaches you. Then you give a little jump and launch yourself down its steep front face, keeping the rear end of the board at your waist and the front end as flat on the surface of the water as you can without actually letting it go under. To avoid collisions with other bathers you can steer to a limited extent by tipping the board down on one side and as you get better at it you can start further out to get a longer ride, but be careful as the sea is definitely rough. What it costs: About 60 cents per board and your car ride out there. Equipment: Get one board each in town before you go. Tips: Do not go out beyond your depth in the breakers unless you are a strong swimmer. Take drinks and sandwiches with you. |

|||

| Overall observation | General

Observation: Basic

paipo boarding in the south Caribbean. The question one must ask is for

how long has the sport been practised and to what extent? Special thanks to John Hughes of the Cocoa Beach Surfing Museum for finding and sharing this story. |

||

|

El Paipo. ca. 1971. El Paipo Kneeboards. Newport Beach, CA: El Paipo Company. |

|||

| The brochure (PDF format) |  |

Pictured

to the left is an excerpt from the front page of this ca.1971 brochure.

The figure captures the full transition of the El Paipo company from a

bellyboarding/paipo board builder to a kneeboarding design and build

company. Four designs are featured in this 5-page brochure, the: (1) El Paipo Standard Model, (2) Fish Family, (3) Gun, and (4) Pocket Mouse. All except the Pocket Mouse are kneeboards. The Pocket Mouse is a large handboard (28 inches). All four boards feature scooped out decks, deck handle(s). and a Fins Unlimited fin box (except for the finless Pocket Mouse). |

|

| Source | The El Paipo brochure ca.1971, on El Paipo Kneeboards was provided by Bill Baldwin, a former shop manager at El Paipo (1970-1972) and shaper and rider at House of Paipo (1968-1970). | ||

|

Elwell, John C., Schmauss, J., and California Surf Museum. 2007. Surfing in San Diego. Charleston, SC: Arcadia Pub. |

|||

| Snippet of cover. |

|

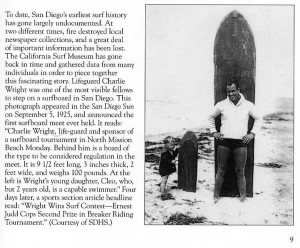

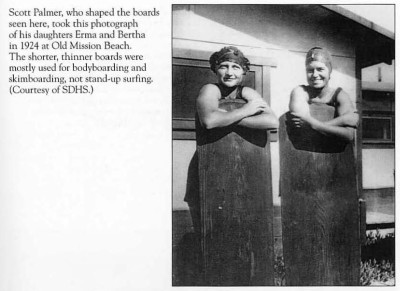

Great effort by the authors and the Californaia Surf Museum in publishing this pictorial history with words. Of relevance to the world of paipo riding are two pictures and captions of bellyboard/paipo boards. | |

|

Estes, Steve. 2022. Surfing the South: The Search for Waves and the People Who Ride Them. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press. |

|||||||||

| Title page and Contents [PDF] and Introductory Chapters |

|

The book is a semi-autobiographical story of spending two summers traveling

along the unsung southern coasts with his young daughter, from Texas to

Maryland, conducting oral interviews with folks having a knowledge of

surf history. For the most part the quest was a contemporary oral

history with surfers along the coasts. Many of the interviewees were

competitive surfers and surf shop owners or active in area surfer

museums or halls of fame. The author grew up in Charleston, South

Carolina, and he earned a PhD at the University of North Carolina.

Estes is currently a professor of history at Sonoma State University in

Northern California. He lives in San Francisco and counts Ocean Beach

as a home break. He mostly rides shortboards but surfed pop-out soft

top longboards during his quest. His daughter sometimes rode a

boogieboard. |

|||||||

| Ch. 6,

pp. 74-96, The Space Coast: Cocoa Beach, FL |

Cocoa

Beach, FL and the Space Coast felt "like Mecca, the East Coast

equivalent of Huntington Beach or Haleiwa." As background (p.75):

|

||||||||

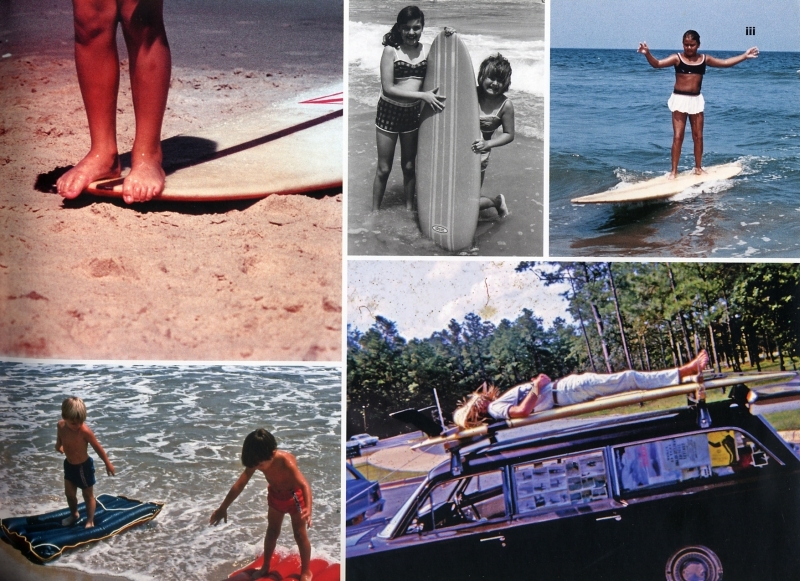

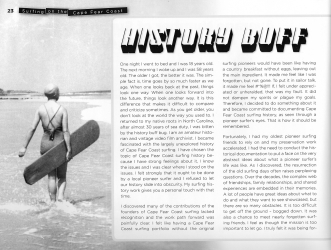

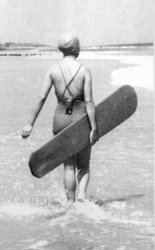

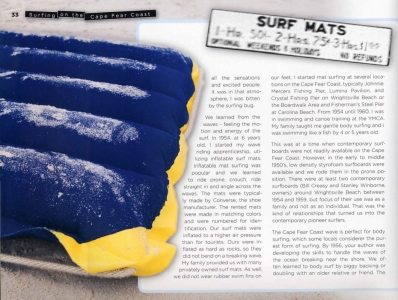

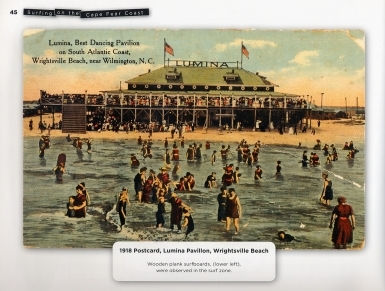

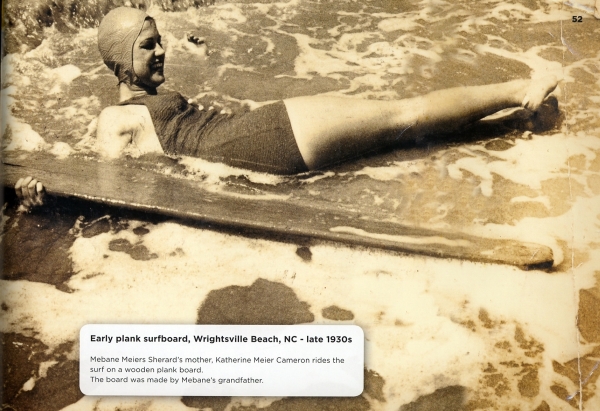

| Ch. 9, pp. 130-144. The Shape of the Past: Cape Fear Coast, North Carolina | The author interviewed Joseph "Skipper" Funderburg, author of a personal history of Surfing on the Cape Fear Coast. Funderburg is one of the first generation of wave riders in Eastern North Carolina. Estes writes,"A historian in his own right, Skipper gave an impromptu lecture on the history of wave-riding and water sports in the Tar Heel State. North Carolinians raced canoes, boats, and rafts in the surf during the nineteenth century. By the twentieth century, some intrepid residents began to ride solid wood planks on their stomachs [emphasis added]." (p. 135).The author then describes photographs found by Funderburg showing local lifeguards aquaplaning on Tom Blake's hollow boards, with fins below the board, in the late 1930s and 1940s. [NOTE: It is not clear whether the lifeguards were waveriding prone, kneeling or standing. We would need to see the photographs.] The author, Steve Estes, then summarizes, "Surfing, as we know it, didn't really arrive in North Carolina until the 1950s and early '60s." [NOTE: Does mean the Gidget era with foam and fiberglass longboards sporting center fins, or the shortboard era of thrusters and multiple fin systems and hull shapes? Do I detect a boardist, or boardism?] |

||||||||

| Acknowledgments and Note on Sources |

The following items are identified as potential future resources in the paipo research project.

|

||||||||

| Overall observation | Bellyboarding,

paipo boards, boogie/bodyboarding, kneeboarding were not on the radar

in this book. The gut reaction is that prone surfing is not real

surfing, or as the author stated, "kook sponge." I will give the author

credit for his honestly in stating his gut reaction and then

reassessing his bias. Boogie or bodyboarding did show up in the index

as I recall, but not bellyboard, paipo or kneeboard. He did mention

several talented bodyboarders at his home break, Ocean Beach in San

Francisco, Calif. Nonetheless, new items were discovered and new areas

identified for examination. The oral histories make for good listening

and/or reading. |

||||||||

|

Farrelly, Midget, and Craig McGregor. 1967. The Surfing Life, As Told to Craig McGregor. New York: Arco Pub. Co. McGregor, Craig., & Midget Farrelly. 1965. This surfing life. London and Adelaide: Angus & Robertson in association with Rigby. |

|||

| Cover, Note & Contents (1.7MB) |  |

Just for the record. Editor's Note: I obtained a copy of the 1965 edition some months after the 1967 edition, and will make notations as appropriate. The author's Note is about half as long but the Contents are the same. The Title page includes the same photograph. Pagination is different, horizontal rather than vertical. | |

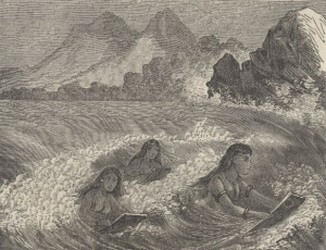

| Page 142 from the chapter, The Story of Surfing (600KB) | The chapter/story begins, "Where did surfing begin? Nobody knows for sure. Ricky Grigg believes that it originated in the southern islands near Tahiti, where the islanders found they could ride the waves lying on small wooden boards or kneeling on them." No citations or further discussion on Ricky Grigg's belief. | ||

| Ch. 15, Other Surfing Methods, including, Mat Riding, Handboards, Belly Boards, The Peipo, and Fins (3.5MB) | Items of note

|

||

| Glossary (1MB) | The following paipo/bellyboard-related terms are listed in the glossary:

|

||

| Overall observation | The book is written in a "popular-style" for a wide audience, but covers all the bases rather well, written from the Australian experience. Chapter (7 pages) is dedicated to body surfing. Note the spelling of "peipo" and that the peipo is classified as a type of belly board. No other changes detected in review of paipo surfing. | ||

|

Ben R. Finney, a leading surfing historican and scholar, published his seminal scholarly work in 1959, and followed that with several scholarly journal articles in multiple languages. In 1966, Dr. Finney wrote his first commercial book on the sport of surfing in conjunction with James D. Houston. Below are a list of surfing-related publications. Finney, Ben R. (1959). Hawaiian surfing, a study of cultural change. Honolulu: University of Hawaii, pp. 135. [thesis]. "This work, an exercise to obtain a Master's Degree, was my first major research on any topic. Although some of my professors were skeptical that I could find enough material or survive to write a thesis, in fact I found loads of stuff on ancient legends, in explorers reports and missionary diatribes, as well as talking with the old timers from Hawai'i, California, Australia and Peru." Finney, Ben R. (1959). The Surfing Community: Contrasting Values Between the Local and California Surfers in Hawaii. Social Process in Hawaii, 23, 73-76. "As a "Coast Haole" from Windansea and Steamer Lane I noted the cultural differences between California and Hawaiian surfers." Finney, Ben R. (1959). Surfboarding in Oceania: its pre-European distribution. Vólkerkundliche Arbeitsgemeinschaft in der Anthropologischen Gesell schaft in Wien. (Viennese Ethnological Bulletin), 2, pp. 23-36. Vienna, Austria. (See below.) "The summer after I received my M.A. I was studying German in Vienna, in preparation for my PhD studies which required that I be able to read at least two other scientific languages besides English. Anyway the editors of the "Viennese Ethnological Bulletin" asked me for an article from my thesis, so I wrote this one about the distribution of surfing around the entire Pacific, not just Hawai'i and Polynesia." Finney, Ben R. (1959, June-September). Ancient surfriding in Tahiti. Bulletin de la Societe des Etudes Oceaniennes, 127 and 128, 53-56. Papeete, Tahiti. Translated from French. <http://www.surfresearch.com.au/1959_Finney_Ancient_Tahiti.html>. See notes for rest of the translation credits. Finney, Ben R. (1959, December). Surfing in Ancient Hawaii. Journal of the Polynesian Society, 68(4), 327-347. Accessed from the journal on the Internet. "I wrote this analysis of ancient Hawaiian surfing for the Journal of the Polynesian Society, a New Zealand publication that is one of the oldest anthropology journals in the world still being published." Finney, Ben R. (1960, December). The Development and Diffusion of Modern Hawaiian Surfing. Journal of the Polynesian Society, 69(4), pp. 314-331. Accessed from the journal on the Internet. In this article, based on work which he undertook for the degree of M.A. at the University of Hawaii, Mr. Finney traces the decline and subsequent revival of surfing in modern Hawaii and discusses the diffusion of the sport to other countries in and bordering the Pacific. Finney, Ben. (1962). Surfboarding in West Africa. Wiener Volkerkundliche Mitteilungen, 5:41-42. No copy available. Finney, Ben R., and James D. Houston. (1966). Surfing, the Sport of Hawaiian Kings. Rutland, Vt: C.E. Tuttle Co. (See below.) Finney, Ben R., & James D. Houston. (1969, August-September). Polynesian Surfing. Natural History, 78(7), Cover, Table of Contents, 4, 26-35, 62, 75. Additionally, "About the Authors" and "Recommended Reading." Margan, Frank, and Ben R. Finney. (1970). A Pictorial History of Surfing. Sydney: Hamlyn. (See below.) Finney, Ben R. and James D. Houston. (1996). Surfing: A History of the Ancient Hawaiian Sport. San Francisco: Pomegranate Artbooks. (See below.) Lemarie, Jeremy. (2017, May 29). Interview with Ben Finney • A Tribute [special editing by John Clark]. The Surf Blurb. Retrieved May 30, 2017, from http://www.surfblurb.com/ben-finney.html? The Surf Blurb is a weekly email magazine, originally created by Joe Tabler and now produced by Jeremy Lemarie. For more information visit the website. |

|

Finney, Ben R. (1959). Surfboarding in Oceania: its pre-European distribution. Vólkerkundliche Arbeitsgemeinschaft in der Anthropologischen Gesell schaft in Wien. (Viennese Ethnological Bulletin), 2, pp. 23-36. Vienna, Austria. |

|||

| Title page and Contents [PDF] and Introductory Chapters Source(s) |

|

"The

summer after I received my M.A. I was studying German in Vienna, in

preparation for my PhD studies which required that I be able to read at

least two other scientific languages besides English. Anyway the

editors of the "Viennese Ethnological Bulletin" asked me for an article

from my thesis, so I wrote this one about the distribution of surfing

around the entire Pacific, not just Hawai'i and Polynesia." |

|

| Ch. 9, pp. 130-133, Body Surfng and Bellyboarding | xxx Of

the four

pages devoted to body surfing and bellyboarding, 2.5 pages cover body

surfing and 1.5 pages are on bellyboarding. No section covers hand

boarding or kneeboarding. Key passages include:

|

||

| Overall observation | xxx Although published in 1970, the first edition is mostly written in a mid-1960s flavor with a longboard orientation except in the chapter "The Boards." There are tons of photos but none of bellyboarder/paipo riders. The terms bellyboard and paipo ("as they are called in Hawaii) are both used. In the glossary defines paipo, but not bellyboard, "Paipo: the Hawaiian term for a bellyboard. See Chapter 9." There is no real discussion of board lengths, widths, thickness or plan shapes. | ||

|

Finney, Ben R. 1959. Surfing in ancient Hawaii. Wellington, N.Z.: Polynesian Society. |

|||

|

Finney, Ben R., and James D. Houston. (1966). Surfing, the Sport of Hawaiian Kings. Rutland, Vt: C.E. Tuttle Co. |

|||

| Title

& Contents (200KB) pp.23-25 pp.32-34 |

|

Just for the

record. (Note: most of the scanned PDF files below range from 60KB to

420KB.) "No one knows who first realized the possibilities of riding the swells that had always been so much a part of island life. It may have been a weary swimmer bounced all the way to the beach in a white boil, or a canoe full of fishermen straining to make shore in heavy seas, who first knew the thrill of racing across the rising slopes. As for when it happened, we can only guess. Simple surfing with a body-board may be several thousand years old, as old perhaps as the settling of the Pacific islands." Terms cited from early European observors included, "wave riding," "surf-riding," or "surf boarding." |

|

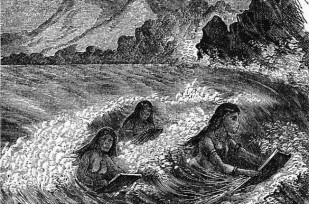

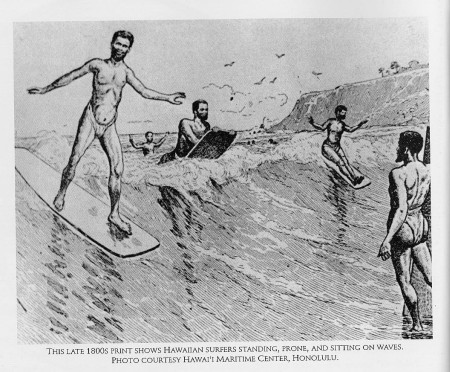

| chapter 2, Pacific Origins | "With one exception, moreover, it is doubtful that wave-riding as a

popular recreation existed anywhere beyond Oceania before the 19th

Century. That one exception is the West Coast of Africa, in areas of

Senegal, the Ivory Coast and Ghana. Near Dakar, Senegal, for example,

African youths and young fishermen regularly body-surf, ride

body-boards and catch waves while standing erect on boards about six

feet long. These Atlantic skills seem in no way connected with the

Pacific, either historically or prehistorically. Evidently it's an old

pastime in west Africa; young Africans were seen riding waves while

lying prone on light wooden planks, as long ago as 1838, long before

surfing began to spread from Hawaii." "Two basic board types are used in the surf. A bodyboard or belly-board is usually from two to four feet long and used as an auxiliary aid in sliding across a wave. The surfer is actually swimming and holding the board in front of him as a planing surface. This is commonly a children's pastime, not an adult sport. True surfing requires a full-sized board, usually eight feet or longer, that can support the rider entirely, allowing him to ride prone, kneeling or standing. Early accounts mention long boards specifically in only two island groups-New Zealand and Hawaii. Some New Zealand boards were six feet long, but because they were only nine inches wide they probably didn't support an erect rider and were ridden prone. Morrison says boards of "any length" were used in Tahiti. Four-foot boards were known in the Marquesas. In early accounts of surfing in Melanesia, Micronesia and western Polynesia, all boards which were mentioned are only a few feet long." |

||

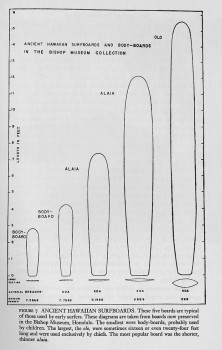

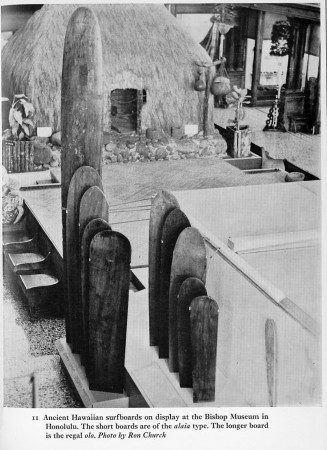

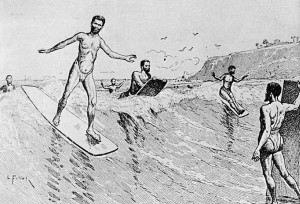

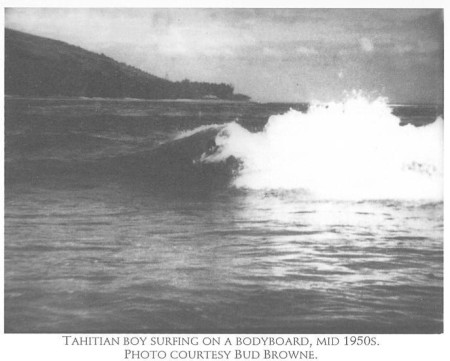

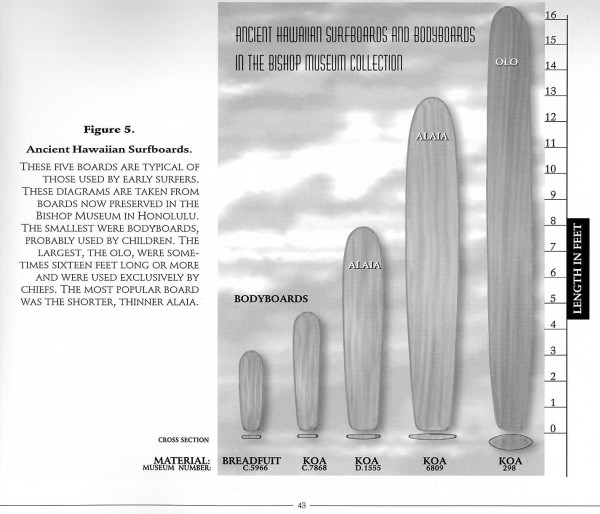

| Some figures from ch.3, Ali`i, Olo & Alaia and ch.5, The Revival | 1- Tahitian boy

surfing on a belly board (click

here) 2- Ancient Hawaiian surfboards on display at the Bishop Museum (click here) 3- The Bishop Museum has the world's largest collection of ancient Hawaiian surfboards (click here) 4- Diagram of surfboards since 1907, arranged chronologically (click here) 5- Diagram of five ancient Hawaiian surfboards (bodyboards, alaias and an olo) (click here) |

||

| pp.63-64 from ch.4, The Touch of Civilization | "Today

all that remains is an occasional youngster skimming through small

waves on a body-board. Not a surfboard is seen on the waves that break

around this fabled south sea island. The changes wrought by western

civilization virtually eliminated a once popular recreation. In recent

years a few surfers have travelled there with modern boards and have

discovered good waves on many beaches. Tahitians are often encouraged

to try a board or to build their own, but their reaction is almost

always the same. It is a children's pastime, they say. No one seems

interested." |

||

| p.82 from ch.5, The Revival | The author espouses a certain superior air of stand-up surfing over riding prone, "During the ride itself the technique of lala, angling, is still the most skillful, and standing is of course the only acceptable way to ride. Although sitting, kneeling and prone riding positions were all popular formerly, such postures are now used only for novelty, amusement or by those who cannot stand." And, "From nineteenth century reports, early surfers seemed content to paddle, catch the wave, stand up and then speed ahead in one direction. New boards and modern imagination have changed this. ... An experienced surfer can thus play the wave as he rides it-speed up, slow down, turn, swerve, change direction, ride in the trough or shoot along its thin crest. He can turn to the left by shifting right foot behind left. He can swerve to the right by placing his foot on the board's right edge and lean in that direction. He can stall by stepping back on the board, or speed forward by walking tothe nose. " Funny that these examples espoused as superior were shortly thereafter trumpted by people riding prone or on their knees, riding tightly in the curl, inside the tube, spinning 360s and el rollos, moving faster across wave faces and performing other more radical maneuvers. Oh well, this was the page that I call the "paipo slam" (a play on words for the Zuma Slam). | ||

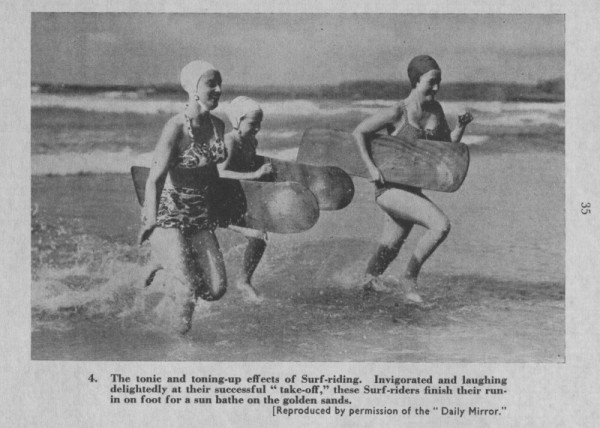

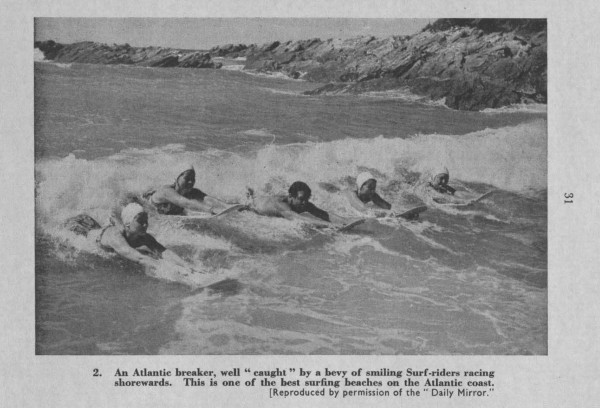

| pp.96-98 from ch.6, Surfing Goes International | "In

New Zealand, for instance, the revival of a long-dead pastime was due

to Australia's influence. As we have seen, surf sports were known to

early Maoris. Canoe surfing, body-board surfing and body-surfing, known

collectively as whakarerere, were all popular pastimes. They

declined and have virtually disappeared, however; and modern surfing in

New Zealand dates from the 1930's when Australian Surf Lifesavers

arrived with skis and cigar boxes." "In 1953 the surf-lifesaving movement was established in England, and, with the unique safety methods came the surfboard, surf-ski and all the oceanic skills developed on Australia's beaches. With its time-honored reputation for fog, foul weather and the frigid English Channel, England seems an unlikely spot for a traditionally warm weather sport like surfing. But the southwest coasts of Devon and Cornwall boast the mildest summer climates in the British Isles... Body-board surfing has been known there since the early years of this century." |

||

| Glossary, Endnote Citations and Bibliography (500KB) | The appendix is

a glossary of ancient Hawaiian surfing terms. Of direct interest are

the following terms:

|

||

| Overall observation | The

book is written in a "scholarly-style" for a wide audience. Finney's

academic research credentials are clearly evident as he broke ground in

becoming a "surfer surfing scholar dude" and collaborated with several

noted scholars and researchers in Hawaii. Although Finney demonstrates

a clear bias towards stand-up surfing this doesn't interfere with

documenting the genesis of prone style riding and its dispersion

throughout the world. What is absent however is any mention of the term

"paipo" (or any of the derivatives of the word such as paepo) despite a

number of adults practicing the sport during the 1950s and early 1960s

in Hawaii (e.g., Wally Froiseth making Pai Po boards in the 1950s). Editor's Note: These PDF files were scanned at 150 dpi resulting in smaller file sizes but also of lesser quality. |

||

|

Margan, Frank, and Ben R. Finney. 1970. A pictorial history of surfing. Sydney: Hamlyn. (see entry under Margan, F., & Finney, B.R.) |

|

Finney, Ben R. and James D. Houston. Surfing: A History of the Ancient Hawaiian Sport. San Francisco: Pomegranate Artbooks, 1996. |

|||||||||

| Contents and excerpt from the Forward |  |

From the Forward, "This was the first book to chart surfing's Pacific origins in the context of Polynesian culture. Its main outline was conceived and developed by Ben Finney as his master's thesis in anthropology at the University of Hawai'i. Much of the material was revised by James D. Houston, who also added new details and interpretations. For this thirtieth anniversary edition, a number of seldom seen drawings and early photos have been added, along with appendixes of vintage writings on the subject," including Lt. James King (Capt. Cook voyages), Jack London, Mark Twain and others. "A few historical and cultural details have been updated (e.g., pronunciation marks for Hawaiian terms and the use of Polynesian place names, such as Rapa Nui and Aotearoa in lieu of Easter Island and New Zealand)." | |||||||

| pp.13, from ch. 1, The Wave, the Board, and the Surfer | "Hawai`i's

gift to the world of sport is surfing-sliding down the slope of a

breaking wave on a surfboard. Long before Captain Cook sailed into

Kealakekua Bay, Hawaiians had mastered the art of standing erect while

speeding toward shore. Riding prone on a wave with the aid of a short

bodyboard was practiced throughout the Pacific Islands, primarily by

youngsters, and probably dates back thousands of years. The Hawaiians

took this ancestral habit, lengthened the boards, refined their shapes,

and developed techniques that moved Lt. James King, in the first